Documenting Source Code

- Intro

- Self-Documenting Code

- Adding Documentation

- Adding Even More Documentation

- Adding Assumptions to the Documentation

- Unit Tests are Also Documentation

- Conclusion

Intro

NOTE: I will use ECMAScript, some JSDoc syntax, and concepts extracted from the awesome How to Design Programs book to exemplify the subject under discussion in this post, but it can be adapted and transferred to any other programming language. The ideas here are more important than the specific syntax for one given programming language.

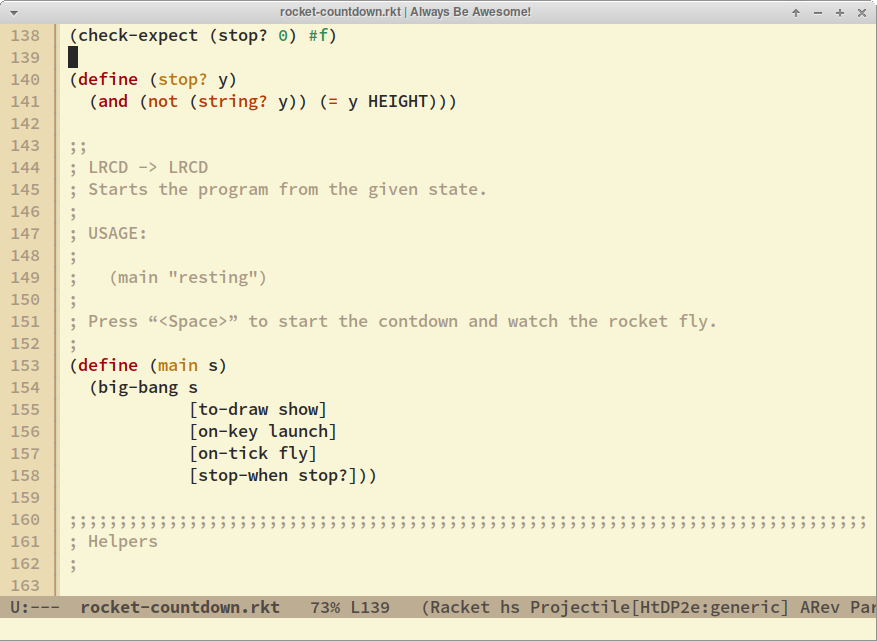

Suppose we have this function:

function sum(x) {

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sum(x - 1);

}

What does it do‽ Given the name ‘sum’ you can most certainly infer it must perform an addition of some sort and that the input x is probably a number. Can you guess what it really does without running it‽ Can you mentally (or on paper) follow the logic and tell the output if the input x is 5‽

Self-Documenting Code

The first order of business would be to give it a more specialized name than the very generic ‘sum’. Let’s try naming it ‘sumFrom1To’:

function sumFrom1To(x) {

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sumFrom1To(x - 1);

}

OK. Now we know that this function, given its more meaningful name, sums numbers from 1 to some given number x. We assume x is a number because we are talking about summing something (or adding something), and that operation is performed on numbers.

Also, note that the name of the function is made more meaningful because of name of the parameter. The meaning of both combined are more clear in context than in isolation. Aloud, it reads like “sum from one to x”. Without the x, it would read “sum from one to…” To what‽ Indeed, the x parameter really helps a lot to understand the function name and purpose and vice-versa.

We could also have named the parameter ‘n’ or ‘num’, or ‘end’, ‘endNum’, ‘upperBound’, ‘upperBoundNum’, etc. In this case I would really go the the simpler ‘x’ or ‘n’ because it is concise and clear enough in context.

Adding Documentation

Human languages are not mathematical (with a precise notation and meaning) and therefore are always susceptible to interpretation. Yet, although we were not explicit about it, we might also infer that it sums all numbers between 1 and the given number x.

That is, “sum numbers from 1 to x” does not mean “sum only certain (even, odd, etc.) numbers from 1 to x.” It mostly likely means all numbers from 1 to 0.

So far, we have not added any explicit documentation to our function. Let us do it now and — to the best of our ability — try to make it useful, concise and precise:

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x.

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

function sumFrom1To(x) {

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sumFrom1To(x - 1);

}

It helps a lot for someone just taking a quick glance at it!

Adding Even More Documentation

Let us now turn aur attention to the parameter x‽ We are basically calculating a sum of a range of numbers here. That poses yet another question: is the range inclusive or exclusive‽ That is, are both 1 and x included in the sum‽ Ranges and things that split strings and arrays have peculiarities regarding the upper bound number. Generally, the lower bound is almost always inclusive, while the upper bound is is sometimes inclusive, sometimes exclusive. It depends on the language or operation being performed.

About Ranges and Indexes

Take Haskell and Ruby and a range from 1 to 3. For the sake of example let us add 10 to each number in the range:

$ ghci

λ> map (+ 10) [1..3]

[11,12,13]

$ irb --simple-prompt

>> (1..3).map &->(e) { e + 10 }

=> [11, 12, 13]

The upper bound of the range is inclusive in both cases. That is, the upper bound is used, included in the computation. However, take this string slicing function in ECMAScript:

$ node --interactive

> 'The Force!'.slice(0, 5);

'The F'

Index 5 is “o”, but it was not included in the result. In this case, the upper bound is exclusive. Ruby behaves the same as ECMAScript when slicing arrays and strings. Haskell take also considers the upper bound not inclusive:

$ ghci

λ> take 5 "The Force"

"The F"

And there you have it! There are some differences in how the edges of ranges and indexes are handled in languages.

Back To Our Documentation

With the discussion above, we can arguably be confident that we’d better be clearer and explicit about x being included in the computation or not. Let’s suppose that after careful consideration and some talk with a colleague, we decided that for this situation we want x to be inclusive, and update our doc comment appropriately:

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x, inclusive

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

function sumFrom1To(x) {

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sumFrom1To(x - 1);

}

We could also use a slight variation on the way to denote the inclusiveness (or not) of x, and write the comment something like this:

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x.

*

* NOTE: x is included in the range.

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

Or perhaps, better yet:

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x.

*

* NOTE: both 1 and x are included in the range.

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

It may look overly cautions and we may have even been redundant about 1 being also inclusive, but better a little precaution than a great regret. It is at least completely clear that both edges of the range are inclusive.

Adding Assumptions to the Documentation

There is one more important point we can tackle before we can definitely say we have written good enough piece of documentation for our function.

Take a look at the base case: it returns 1 when x === 1. Also note that we are recursively invoking the function, decreasing 1 each time for the purpose of reaching the base case and avoid an infinite recursive chain of calls that would lead to a stack overflow. But what happens if we call the function with 0 or a negative number‽ Exactly! An infinite loop culminating in a call stack overflow!

We have a few courses of action to opt for. One would be to decide that if our function is passed a number less than 1, then it would always return 0, or NaN, or throw an exception, or whatever else we might find appropriate.

Another approach would be to settle on requiring client code to guarantee they’ll pass the expected arguments and blow up in their faces if they do not input valid values.

No matter what we choose, our function would be best understood and used by client code if we documented about the expected input assumptions.

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x.

*

* NOTE: both 1 and x are included in the range.

*

* ASSUME: Input is valid, x >= 1.

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

function sumFrom1To(x) {

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sumFrom1To(x - 1);

}

With that, more or less we wash our hands if the function is invoked with x <= 0 and callers are responsible providing the expected input. It is a design choice. It is not inherently the correct or wrong choice, though.

We might also change to a combined approach to prevent infinite recursive calls and still document what is expected. So, besides adding that pice of info to the documentation, we can also improve the resilience of our function a little more and handle the case for when x < 1.

/**

* Sum all numbers from 1 to x.

*

* NOTE: both 1 and x are included in the range.

*

* ASSUME: Input is valid, x >= 1.

*

* @param {number} x

* @return {number}

*/

function sumFrom1To(x) {

if (x < 1) return NaN;

if (x === 1) return 1;

return x + sumFrom1To(x - 1);

}

By reading the comment and code, it is explicitly saying that we expect x >= 1, but the function is also documenting itself in code that if x is less than 1 then NaN is returned.

One could argue that all code, no matter how complex, is self-documenting. You read the code, understanding what it is doing, and that means it is self-documenting. So, why is something considered self-documenting, while others seem to require documentation in form of comments‽ There is no single correct answer for this question. One should make use of common sense and decide for each case what seems to warrant extra information in form of comments.

Unit Tests are Also Documentation

One could also argue that like TDD, writing documentation for your code makes you think more clearly and responsibly about what you are doing. I am strongly in favor to the idea that TDD, documentation (perhaps in the form of DDD) and coding itself all combined make up for the best possible outcome in terms of code quality, long term maintainability, resilience, and usability of a code base. Add pair programming to that trio and we have the four pillars of programming enlightenment. 😂️

When you are TDDing, it makes you think about edge cases and situations that would slip through your fingers would you just code the solution to the problem, the actual implementation. If you document what you are writing, it also opens up possibilities and questions that would sometimes remain unearthed.

Each of these steps bring their value to the process and they form a mutual symbiotic relationship.

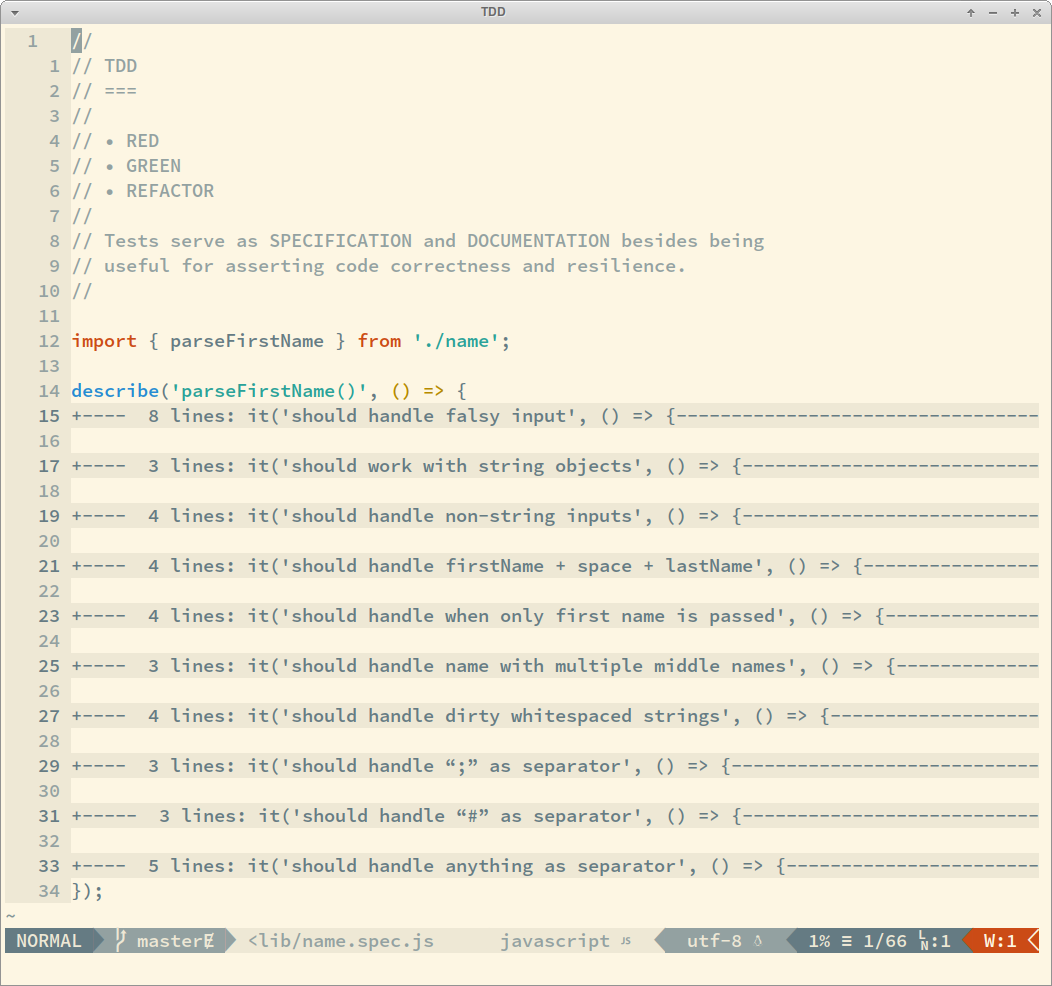

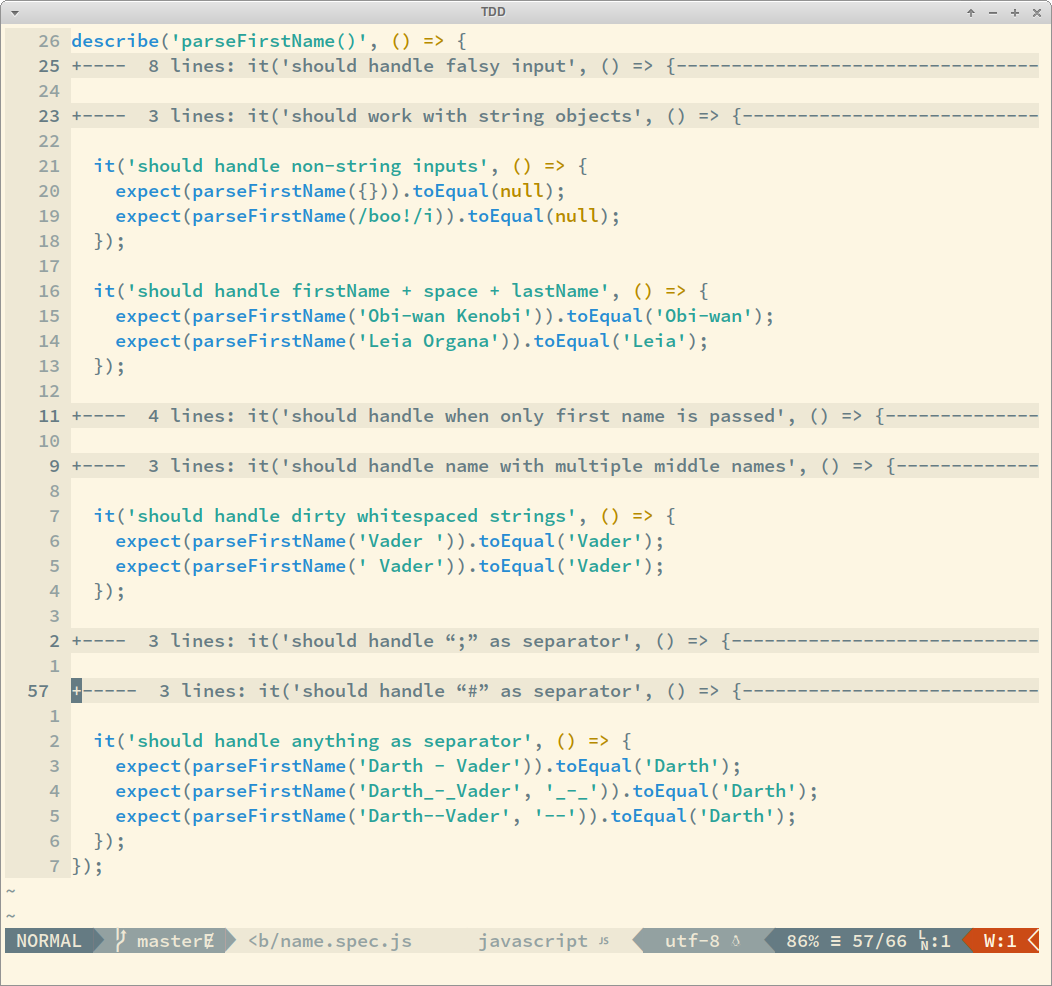

Another thing that unit tests do for us is to serve as specification and documentation about what features and behaviors a piece of code has. Each test case documents one feature, edge case, how invalid input is handled, etc.

Take a look at an example of how unit tests can give a quick overview of what a function does, how it handles things, etc.:

By reading those lines, you see that this function handles non-string inputs, strings objects (not just literals), strings padded with whitespace, etc. And if you read the code of the test cases, you would see what to expect for output given each kind and example of input.

One more time to drive the point home: unit tests make up for good specification and documentation too!

Conclusion

This is a somewhat controversial topic. Some people who have read Clean Code will say any comment is a sin, and it means the code is not good, readable and/or understandable enough. Even when a piece of code is easy to figure out, you may want to generate searchable and navigable documentation using tools like JSDoc, RDoc, HadDoc, etc. Use your best judgement when writing code and documentation.